Disability Justice

Disability justice, termed in 2005 by disabled queer women of color activists—including Patty Berne and Mia Mingus—seeks to address ableism and center people who experience intersectional oppression. Disability justice is a framework that values accessibility, self-determination, and the expectation of difference in ability, identity, and culture. In this framework, there is no “normal” and “other,” but rather all people are equally entitled to access and self-determination, which is defined by each individual's needs. This framework works antithetical to the status quo, which promotes individual meritocracy based on the ability to succeed in a predetermined environment.

As Patty Berne writes, a disability justice framework understands that: “All bodies are unique and essential. All bodies have strengths and needs that must be met. We are powerful, not despite the complexities of our bodies, but because of them. All bodies are confined by ability, race, gender, sexuality, class, nation state, religion, and more, and we cannot separate them.”

We offer the following definitions for clarity:

Dis/ability - Refers to a person’s physical and/or mental capabilities in relation to the capacities deemed as valuable and ideal in a particular historical and cultural context. Physical and mental health are major components of dis/ability, and ability is not always explicitly visible to other people.”

Ableism - Discrimination against people with physical, intellectual, and/or psychiatric disabilities. Ableism, like many forms of discrimination, occurs in many different ways. The assumption that people with disabilities are completely helpless, for example, can manifest in strangers completing tasks for disabled people without asking for consent, referring to people as “suffering” from their condition(s), and using the term ‘wheelchair-bound’ to refer to someone in a wheelchair. Often, attempts to make systems, architecture, technology, etc. more accessible either fall short or overcompensate, because yet another form of ableism excludes people with disabilities from positions of power, adequate resources, and the ability to make decisions for themselves and their community.

Meaningful Inclusion: J to draft

In the United States, people with disabilities are a protected class under the Americans with Disabilities Act; this act provides legal protections against employment and other discrimination. Despite this, we still see both employment and discrimination negatively impact people with disabilities, including those with physical and cognitive disabling conditions. Additionally, it is nearly impossible to live solely off of disability income; this drives more people into sex work and other professional and gig services.

People living with disabilities who work in the sex trade choose to do so for the following reasons:

Flexible work schedule to accommodate one’s own needs

Option to work from home if doing digital forms of sex work

Access to supplemental income

Feeling valued as an adult possessing a sexual identity and erotic appeal

Increased independence

“Nothing About Us Without Us” is a slogan that originated within the disability rights movement. It asserts that persons with disabilities must control decisions affecting their lives.

Accessible Work & Livable Wages

“Sex work and disability are intrinsically linked. People with disabilities are marginalized by society and subjected to stigma and disdain. The disabled often cannot work a physically strenuous job or sustain a long workday and a rigid schedule. Throughout the ages sex work has afforded the disabled a flexible means to earn a living and to survive in an inaccessible and prejudiced world.”

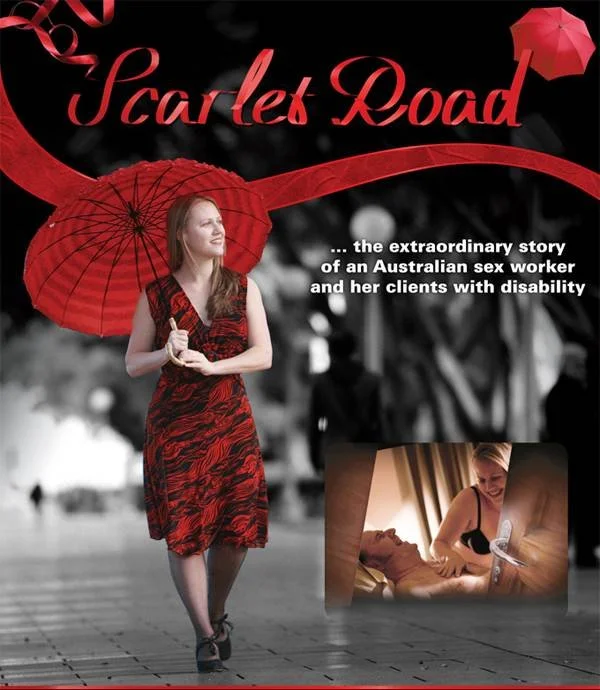

Scarlet Road is a 2011 documentary that explores the life of Australian Rachel Wotton, a sex worker who is based in New South Wales (where prostitution is decriminalised) and sells sex to clients who have disabilities.

“The way our culture infantilizes and desexualizes disabled adults is a travesty. Sex workers can serve as a bridge for disabled clients, helping connect them to their bodies and sexuality in a safe away. I am truly grateful for the opportunities I have had to work with disabled clients, and for the bonds that I’ve forged with them over time.”

Recognizing Intimacy Needs for Adults with Disabilities

For some people living with disabilities, finding opportunities to experience intimacy can be challenging. Persons with disabilities are often treated as though they are asexual. In countries where sex work is criminalized, such as the USA, people with disabilities seeking to access the professional services of an adult sex worker can be arrested and prosecuted for soliciting prostitution. However, in several states in the US, sexual surrogacy is recognized and distinguished from sex work by the inclusion of a therapist and a clinical model. Sex surrogacy differs from traditional sex work in that it’s goal is to help a person overcome a sexual challenge, whereas sex work can center entirely on the goal of experiencing of touch, intimacy, and sex with another consenting adult. In countries with more liberal sex work policies, organizations such as Touching Base can exist, which cater to the needs of clients with disabilities.

Learn More:

(Dis)ability and Sex Work Decriminalization - DSW (decriminalizesex.work)

Sex Work & Disability: Intro to a Spexial Issue - Disabilities Study Quarterly

“Sex Work is Work” Say Sex Workers with Disabilities - Open Democracy

Sex Work as Work & Sex Work as Anti-Work, Hacking/Hustling

Sex Trade Security & Adversity - Liz Elytra, Spokes Hub graduate

Secret Life of an Autistic Stripper - Reese Piper

Meet Melanie & Chayse: A Disabled Woman & Her Sex Worker - BBC